Table of Contents

Objectives

- Become familiar with the different styles of debugging

- Become familiar with GDB through VSCode and the terminal

- Gain exposure to the process of analyzing the assembly of a compiled C program

Getting Started

Use the GitHub Classroom link posted in the Learning Suite for the lab to accept the assignment. Next, ssh into your Raspberry Pi using VSCode and clone the repository in your home directory. This lab should be done in VSCode on your Raspberry Pi.

Overview

Debugging is an essential part of software development, and debugging in C or assembly requires you to be able to use a combination of tools and techniques to identify and fix errors in the code. The process of debugging involves identifying the cause of the problem, developing a hypothesis, testing the hypothesis, and implementing a solution. By using intentional and incremental programming, print statements, and GDB, you can effectively debug your programs and ensure that they run as expected.

Intentional and Incremental Programming

Intentional and incremental programming are two important mindsets to have while diving into software development. Intentional programming is a mindset that prioritizes writing code that is clear, concise, and easy to understand. In other words, the emphasis is on writing code that accurately reflects the your intentions rather than trying whatever and seeing if it sticks. Approaching a solution in code intentionally will inevitably be a lot more productive and easier to maintain and extend in the future.

Incremental programming, on the other hand, involves dividing the solution you are trying to create into small, manageable chunks that can be developed and tested individually. This allows for a more flexible, iterative approach to software development. This means that changes can be made easily and quickly, without having to completely overhaul the entire solution when something crashes.

Handling large amounts of data in C is no small task (as you will see in the next lab). It requires attention to detail and a good understanding of the code you are writing and what it does. As the projects in this and other programming-centric classes become more complex and involved, it is important to remember that the best line of defense against buggy code is a good offense: intentional and incremental programming.

Trace debugging

Trace debugging is a technique used to identify the root cause of a problem in a program by logging the values of variables and other information at specific points in time. This trace data can provide insight into how your program is actually behaving.

One form of trace debugging is performing manual checks on data by adding printf() statements to a program. Printing out the value of a buggy variable every time it gets modified can help you track the changes and note where the algorithm goes wrong.

void modify_string(char * in_str){

// Implementation of function here

// ...

}

...

printf("Original Str:\t%s\n", original_str); // <--- Trace debug print statement (sees the original string value)

modify_string(original_str);

printf("Modified Str:\t%s\n", original_str); // <--- Trace debug print statement (sees the modified string value)

And that’s really all there is to this method! You’ll be surprised to see how effectively simply logging/printing variable values as you go can ensure a smoother development experience. By using trace debugging, you can quickly identify and fix bugs, improve the performance of your program, and improve the overall reliability of your software.

Using a Logging Library

However, using just regular printf statements has some problems. For example, if you have a lot of print statements in your code, it can be difficult to keep track of them all. And when you are done debugging, you have to go back and remove all the print statements you added.

Rather than putting print statements everywhere, you can use a logging library to help you debug your code. Using a logging library can make it easier to log messages to the console and can provide additional features such as logging levels, timestamps, and the file location/line number where the log message occurred. Logging libraries also give you control over when the log messages are written to the console, allowing you to filter out messages based on their severity or other criteria. One such library is log.c. This library provides a simple logging interface that you can use to log messages to the console. We have provided the log.c and log.h files in the lab repository. To use this library, you will need to include the log.h header file to the top of your code:

#include "log.h"

and link the log.c file when you compile your program:

gcc main.c log.c

To use the logging library, you can call the log_* functions to log messages to the console. For example, you can use the log_info function to log an informational message:

log_info("This is an informational message");

It will output something like this:

11:56:31 INFO main.c:9: This is an informational message

You can also use the log_debug, log_warn, and log_error functions to log debug, warning, and error messages, respectively. log_* takes the same arguments as printf (except it adds a newline for you!), so you can use format specifiers to include variables in the log message:

int value = 42;

log_info("The value is %d", value);

In the lab files for this repository, there are three files of interest: main.c, math.c, and math.h. Buggy functions have been included in the math.c file. Your job is to debug them using the trace debugging method and ensure that all of them work properly. To compile the program, you must pass all the C files to gcc:

gcc main.c math.c log.c

Answer the questions in the README.md file as you debug math.c.

Using a Debugger

While trace debugging may seem like the most practical way to address small bugs or issues in your code, sometimes it is not enough. Have you every printed out the contents of a double or even triple-nested for loop and tried to find out where your logic went wrong? Sometimes there are so many values to test or the code gets so complicated that having too many print statements makes things even harder.

The simple solution to this is to use a debugger! A debugger is a program that controls the execution of a program, and allows us to pause it whenever we want and examine the values of variables and how they change during runtime. For this class we will be using the GDB debugger. To ensure it is installed on your Pi Z2W, run the following command:

sudo apt install gdb

According to their homepage, “GDB, the GNU Project debugger, allows you to see what is going on `inside’ another program while it executes – or what another program was doing at the moment it crashed.” This is the default program we will be using to debug the code in this class. This program has several modes of operation, including a terminal and graphical interface. You will be using GDB for the Bomb programming assignment, so it is worth spending some time now to get familiar with it.

VSCode C/C++

More modern tools like VSCode have built-in extensions to interface with GDB and provide a more modern experience. To use this, VSCode requires the “C/C++” extension. You should have installed this in the last lab, but if you haven’t, do so using the following steps. These steps should be run from the VSCode session that is connected to your Raspberry Pi:

-

Click on the Extensions button on the left-side menu.

-

In the search bar, type “C/C++” and select the “C/C++” extension by Microsoft.

-

Click the Install button to install the C/C++ extension. If you see a Disable button, that means you have already installed the extension.

Once you have ensured the extension is installed, open the main.c file (if it is not open already). Next, click on the play button with bug in the upper right corner. If your debugger was configured properly, you should not see any errors and a new debugger view should show. It takes longer than you might expect on the Raspberry Pi. Once it is down loading, you should see a menu pop up in the middle top of your screen. These are the controls that will help you run through your program.

Follow the corresponding questions on the README.md for this lab as you learn the following techniques of graphical debugging.

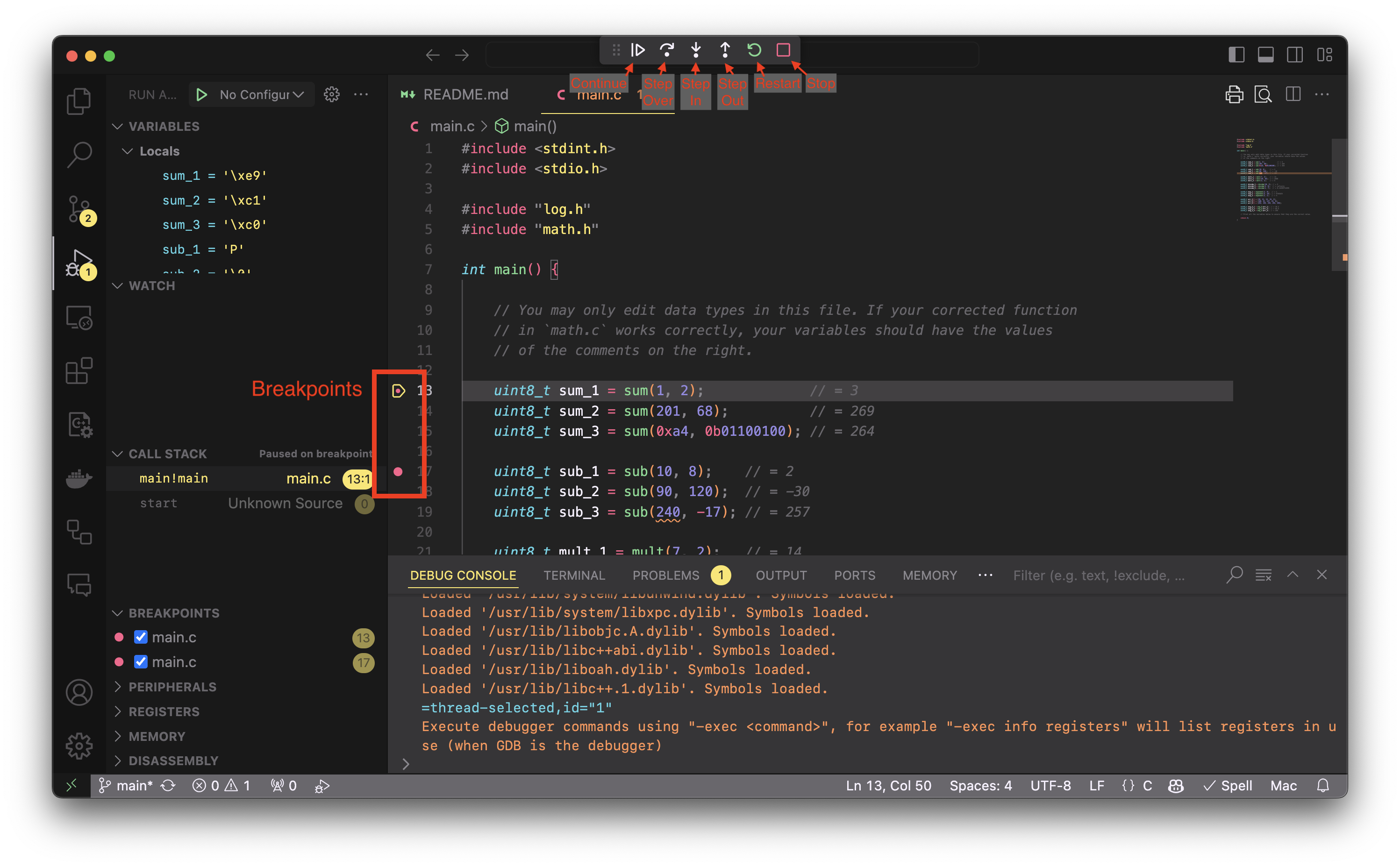

Breakpoints

A breakpoint is a point in the code where the debugger stops the execution of the program. Breakpoints can be set in VSCode by clicking next to the line number of the code that you want your debugger to pause on. Once the program has stopped at a breakpoint you can step through one line at a time.

Step Over

Stepping over a function means that you will call/execute the full function and receive its outputs in one step. If you are certain that a function is working well or you do not want to step into system/library functions, use this option. This is done by clicking on the button with the arched arrow and circle.

Step In/Out

If you come across a function that you want to examine, put a breakpoint on where it is called. Then when you reach the paused line, click on the down arrow in the debug ribbon at the top of the screen. This will allow you to look at how the function is executing. To finish the function and continue the flow of the program, click on the up button.

Answer the questions on the README.md and don’t forget to include screenshots.

Analyzing Assembly

This exercise will be done on the unknown binary in your lab repo.

Not only can you build your project to analyze the source code, you can also use it to analyze the machine instructions (also called assembly instructions) that are getting passed to the processor. This is useful, especially in digital forensics, penetration testing, and reverse engineering. We will be doing this alot later in the Bomb and Attack Programming Assignments!

Analyzing assembly in VSCode tends to be a little trickier and require you to use gdb in the terminal. You can get started by typing in your terminal

gdb unknown

Once you are inside of the command line version of gdb, you will see another shell that looks something like the following:

(gdb)> _

To view the assembly instructions of the file, type in layout asm. To view the register values (or hardware processor variables - you’ll learn more about this later on), type in layout reg. You will want to run these commands every time you bring up gdb.

Some helpful GDB commands to get you going:

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

break or b

|

Sets a breakpoint on function name. |

print varname or p

|

Prints out the value of the variable varname. |

step or s

|

Step through your code. Similar to step into. |

next or n

|

Step program, proceeding through subroutine calls. Similar to step over. |

continue |

Run to the next breakpoint |

run |

Run your loaded gdb code |

These are just a few of the commands, some helpful resources have been provided in the links at the bottom of the lab.

To debug this program, you might run something like this in GDB:

layout asm

layout reg

break main

run

This sets up your GDB session and puts a breakpoint at the beginning of main. It then runs the executable, running until the program finishes or until it hits a breakpoint.

In this exercise, you are expected to apply your knowledge about debugging that you learned in the last section to the unfamiliar environment of assembly. Answer the corresponding questions on the README.md file to finish this section.

Submission

-

Complete all the activities and answer the questions in the

README.md. -

To successfully submit your lab, you will need to follow the instructions in the Lab Setup page, especially the Committing and Pushing Files section.

-

To pass off to a TA, show the output of your debugged program using the logging library.