Table of Contents

Quick References

These links are also provided throughout the lab report when needed.

Part 1: Getting Started

Warning: Please don’t download a bomb before the start date listed on the LearningSuite schedule. If you do, your bomb may be accidentally deleted by the server when the start date passes.

Additionally - this Lab can be very difficult if you don’t understand what’s going on. Make sure you read all the documentation before trying to do the lab!

Storyline Introduction

The nefarious Dr. Evil has planted a slew of “binary bombs” on the ECEn Department’s Digital Lab machines! Each of these bombs is a program that consists of a sequence of phases. We managed to recover the main.c file that he used, but we couldn’t recover the code contained in the phases. We do know however that each phase expects you to type a particular string on stdin. If you type the correct string, that phase will be defused and the bomb will proceed to the next phase. Otherwise, the bomb explodes by printing “BOOM!!!” and then terminating. The bomb is defused when every phase has been defused.

There are too many bombs for us to deal with, so we are giving each student a bomb to defuse. Your mission, which you have no choice but to accept, is to defuse your bomb before the due date. Good luck, and welcome to the bomb squad!

First Things First

-

You must complete this lab on one of the Digital Lab computers. The bomb files are specifically compiled for the architecture used on the digital lab machines, and they will not run elsewhere. Because all your files are stored in a virtual J Drive connected back to CAEDM, it doesn’t matter which computer you log into. You can either:

- Go physically into the lab and use one of the digital lab machines (make sure that another class is not in session)

- SSH into a Digital Lab machine from your own machine and run GDB (See Appendix A for SSH instruction).

-

Grading for this Lab: This lab is worth 70 points. Each time a phase is diffused, your score increases. The phases are weighted according to the following table:

Phase Point Value 1 10 2 10 3 10 4 10 5 15 6 15 Total 70 Be careful! Each time that the bomb explodes, you will lose 1/2 a point (up to a max of 20 points). If you have exploded your bomb several times, you can download another bomb and try again. Your highest scoring bomb will be selected as your grade. Keep in mind that the phases of the bombs are randomly generated, meaning downloading a new bomb requires starting over from phase 1 again. Its better to not let it blow up in the first place!

You can see your current score by looking at the Bomb Lab Scoreboard which can also found on Learning Suite.

Important Resources to have

These two are absolutely must-haves when it comes to GDB and understanding assembly. The x86 Reference Sheet is also extremely helpful if you are studying for Midterm 2!

- GDB Quick Reference - A list of all the GDB commands you’ll need (see also Section 4: Using GDB as well). The most important commands are highlighted, but depending on how you go about diffusing the bomb, you may want the other ones as well.

- x86-64 Reference Sheet - This sheet contains a very succint guide to all the basic facts of understanding x86 Assembly. Use this for understanding assembly commands, register names and jobs, and how to do math with registers.

There are also some additional resources listed in Appendix B that you may find helpful.

Part 2: Download and Unpack The Bomb

Please make sure you are in the digital lab for this step! To obtain your bomb, go to the Bomb Lab Download page here or on Learning Suite. Follow the instructions on the web page (fill out a bomb request form, and the server will deliver a custom bomb to you in the form of a tar file named bombK.tar, where K is the unique number of your bomb.)

You have to have the bomb stored on your J-drive for a digital lab machine to run it. If you downloaded it onto your own computer, you’ll have to use the scp command (something we won’t cover here) to copy it to your J-drive, or just download a new one on a digital lab machine.

Save the bombK.tar file to a directory in your J-drive in which you plan to do your work. Then, open a terminal, navigate to the tar file, and give the command: tar -xvf bombK.tar. This will create a directory called ./bombK with the following files:

- `README`: Identifies the bomb and its owner.

- `bomb`: The executable binary bomb.

- `bomb.c`: The main file we recovered - the bomb’s main routine and a friendly greeting from Dr. Evil.

While you are unpacking things, we recommend that you also look at Appendix C: Using Objdump for some additional things you can do to get some basic information out of your bomb before you start diffusing it.

As mentioned in the grading section above, you can download another bomb at any time. Please do not flood the server with requests. Only your highest bomb will be scored.

If the server is not working, wait 15 minutes and try again (it resets itself on a period of 15 mins). If the issue persists, contact your instructor.

Part 3: Defuse Your Bomb

This is the main task of the lab.

You must complete this lab on one of the Digital Lab computers. In fact, there is a rumor that Dr. Evil really is evil, and the bomb will always blow up if run elsewhere. We have identified several other tamper-proofing devices also built into the bomb, so be careful and follow our guidelines to make sure you protect yourself!

To defuse your bomb, run it and correctly give the six required passwords or “phases”. To run the bomb, you can use the command

./bomb

However, since you do not know any of the passwords (and are highly unlikely to guess them), we strongly advise you instead use a debugger tool (GDB) to disassemble your bomb and step through the code.

Although phases get progressively harder to defuse, the expertise you gain as you move from phase to phase should offset the increasing difficulty. However, the last phase will challenge even the best students, so please don’t wait until the last minute to start.

Instead of running it by hand, you can also run passwords through your bomb using a text file. The bomb ignores blank input lines. For example, if you ran your bomb using

./bomb psol.txt

it would look for psol.txt and read it line by line until it reaches EOF (end of file), and then ask you for any remaining inputs through stdin. We aren’t sure why Dr. Evil added this feature, but it allows you to not retype the solutions to phases you have already defused.

To avoid accidentally detonating the bomb, you will need to learn how to step through the assembly code at the instruction level and how to set breakpoints. You will also need to learn how to inspect both the registers and the memory states. One of the nice side-effects of doing the lab is that you will get very good at using a debugger, a crucial skill that will pay big dividends the rest of your career.

We do make one request: please do not use brute force! You could conceivably write a program that will try every possible key to find the right one. But this is a bad idea for several reasons:

- You lose 1/2 point (up to a max of 20 points) every time you guess incorrectly and the bomb explodes.

- Every time you guess wrong, a message is sent to the bomblab server. You could very quickly saturate the network with these messages, and cause the system administrators to revoke your computer access.

-

We haven’t told you how long the strings are, nor have we told you what characters are in them. Even if you made the (incorrect) assumption that they all are less than 80 characters long and only contain letters, then you would have 2680 guesses for each phase, or

157713125193403080417654809081334009543781200490267680112072492357238610672339306461267146463217189220266463461376 guessesThis would take a (very) long time to run, even at

100,000,000,000guesses per second:5.00105039299223365099108349446137777599509133974719939472578... × 10^91 milleniaand you will not get the answer before the assignment is due.

When you have completed the assignment (fully or partially) submit the answers to your bomb in the assignment on LearningSuite.

Part 4: Using GDB

GDB, or GNU Debugger, is a command-line tool available on virtually every platform, designed for debugging programs in languages like C and C++. It allows you to trace through a program line by line, examine memory and register contents, and inspect both source code and assembly code. For our purposes GDB is essential because it will allow you to reverse-engineer the binary bomb file without access to the original source code. By setting breakpoints, monitoring memory changes, and examining assembly instructions, you will systematically analyze the program’s behavior, identify the required inputs, and progress through each bomb “phase” safely.

While we won’t go diving into assembly code or how to analye it for the passwords, we will provide some references and tutorials for the basic usage of GDB. As you read through this, try to focus on learning what options you have in GDB for analyzing code, so that when begin your bomb, you can use the tools below to take intentional steps towards debugging instead of guessing.

Set up your workspace

Whenever you run GDB, you should make sure that you do it in a terminal that has enough space to show you the code and the registers all at once. While working on the bomb lab, it is often helpful to have your screen divided in half with terminal and browser as follows:

This setup provides a nice balance between having space to see what’s happening in GDB, and having another window to read documentation, etc.

It is also strongly recommended to have second tab open in your terminal (in case you need to run other commands outside of GDB) and to keep pen and paper on hand for taking notes on the code and writing down important values.

Opening GDB

to open GDB, simply type:

gdb bomb

while you are in your bomb folder. From here, your terminal will spit out a few lines:

❯ gdb bomb

GNU gdb (Ubuntu 12.1-0ubuntu1~22.04.2) 12.1

Copyright (C) 2022 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

License GPLv3+: GNU GPL version 3 or later <http://gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html>

This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it.

There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law.

Type "show copying" and "show warranty" for details.

This GDB was configured as "x86_64-linux-gnu".

Type "show configuration" for configuration details.

For bug reporting instructions, please see:

<https://www.gnu.org/software/gdb/bugs/>.

Find the GDB manual and other documentation resources online at:

<http://www.gnu.org/software/gdb/documentation/>.

For help, type "help".

Type "apropos word" to search for commands related to "word"...

Reading symbols from bomb...

(gdb)

This is gdb. Notice that your cursor is now prefixed by (gdb) instead of the normal $ that comes with bash. Anything you type into terminal will now be running GDB commands, not terminal commands.

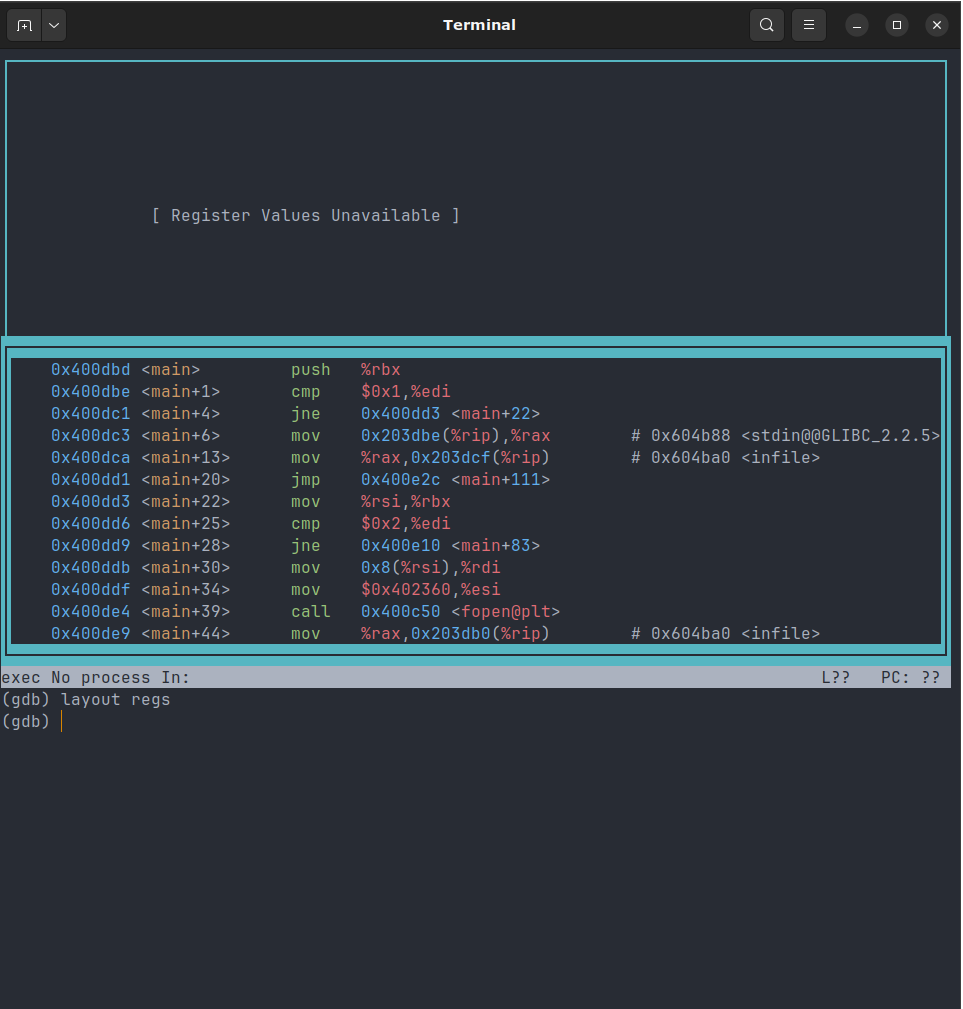

Even though you have GDB open, it still doesn’t look any more helpful than it did before. Let’s change the layout to be more useful by typing

(gdb) layout asm

(gdb) layout regs

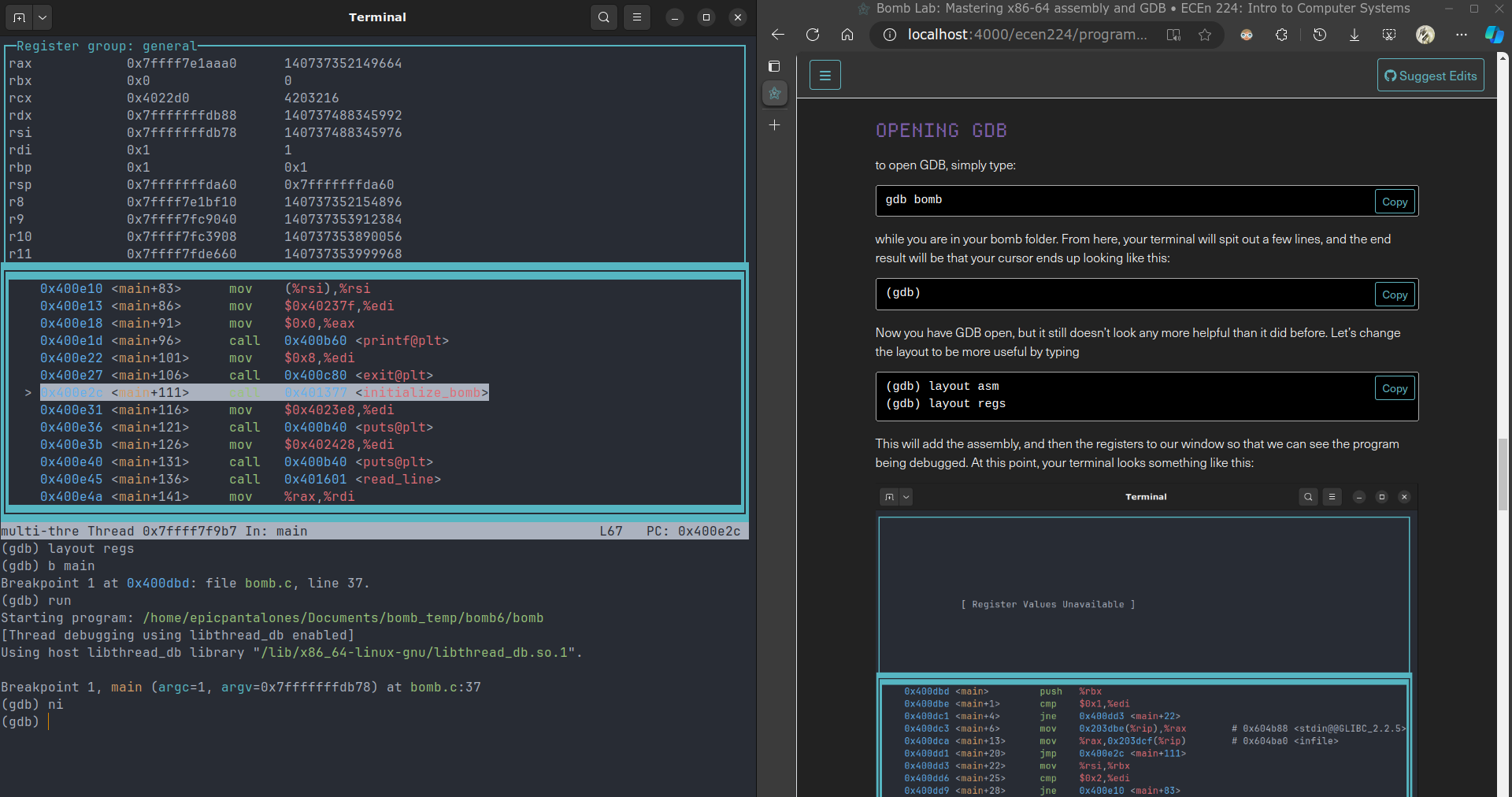

This will add the assembly, and then the registers to our window so that we can see the program being debugged. At this point, your terminal looks something like this:

Now that you have GDB set up, you can start debugging the program. The next few sections will tell you how to do several things in GDB that you will use to debug the lab.

Running & stopping GDB

Note: Before running your bomb, you should read the other sections, which teach you how to protect yourself against explosions.Running the code without understanding how to stop it will likely result in lost points.

Running your program

If you want to run the bomb, all you have to do is type

(gdb) run

From here, you should see your assembly and register panes jump into action! You will also notice that your output pane begins acting both as your input to the program and as your input to the debugger. You can tell when you are talking to the program or the debugger by looking to see if the active line has a (gdb) at the beginning. If it does not, then you are entering input to the bomb. Be careful not to accidentally give debugger commands as your input!

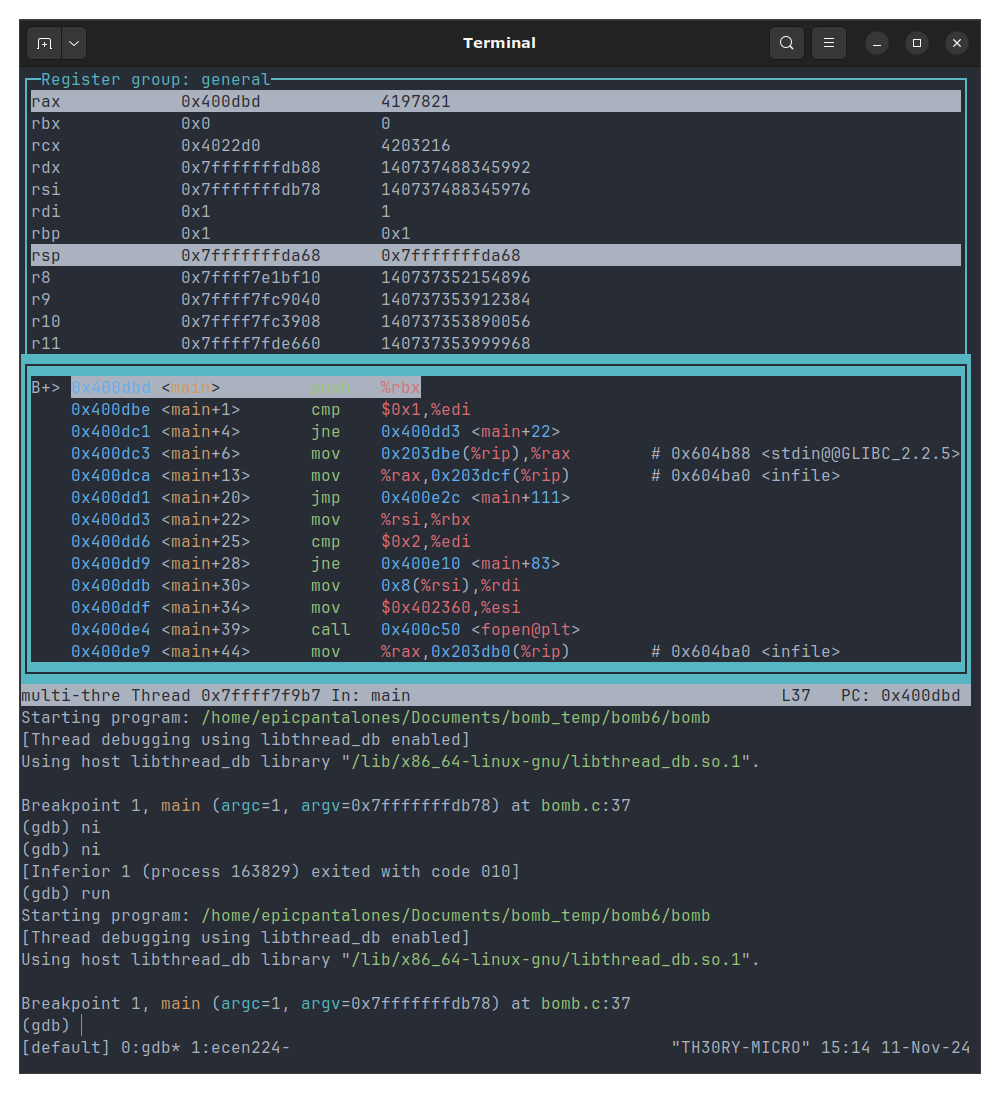

Here’s an example of GDB running the very beginning of the program.

In the assembly pane, the white highlighted line is the line about to be run, meaning that instruction has not executed yet. In the registers pane, each of the highlighted registers were changed by the last instruction, i.e. the one you just ran. We use these two pieces of info to deduce the state of the ptogram at any given point in time.

Stopping your program

If you want to stop the bomb, all you have to do is type

(gdb) kill

which will then ask (to which you respond y)

Kill the program being debugged? (y or n)

It will then say [Inferior 1 (process 34507) killed] (the number will not be the same) which means the program is no longer runnning. This, in combination with breakpoints, is how you prevent the bomb from exploding. If you are panicked and you cannot figure out how to get the program to stop, you can also type quit to quit GDB entirely, or just close the active terminal session. As long as the code in the function that explodes the bomb does not run, you will not lose any points.

Important Notice! Everytime you quit GDB (by closing terminal or typing quit, all your breakpoints will be removed). Try to avoid closing the program unless you are done for the day.

Helpful Tip: using a text file to pass phases quickly

When you run the bomb in GDB, you can give command line arguments just as you would in the regular command line. As mentioned above in Section 3, you can give the bomb a command line argument that will allow you to put in several passwords at once. You will see why this is useful as soon as you have 1 or 2 phases complete. To pass command line arguments in GDB, just add that argument to the end of the run command:

(gdb) run psol.txt

This is the same example in Section 3, and will run the debugger with all the solutions in psol.txt. We recommend that you keep a seperate terminal window open so that you can write to that text file without having to close GDB.

Stepping through code

Once the code is running, you will need to step through the code at various intervals in order to make sense of what’s going on. Here are the descriptions of the basic movement commands you can use in GDB. They are listed in order from “smallest” movement to “biggest.”

-

stepi <count>- Also known assi; Step Instruction. Runs count instructions at once, stepping into function calls. Default for count is 1. -

nexti <count>- Also known asni; Next Instruction. Runs count instructions at once, but does not step into function calls. Default for count is 1. -

finish- Runs until the current function finishes, and stops when it returns to the caller. -

until <expression>- Runs until expression is hit, a memory address of some sort. See Epxressions in GDB for more info on how those work. -

continue- Also known asc. Runs code until the next break point is hit. Be careful with this command; using it carelessly can easily lead to you stepping too far and exploding your bomb.

Setting breakpoints

Important Notice! Everytime you quit GDB (by closing terminal or typing quit, all your breakpoints will be removed.) Do not quit your session of GDB unless you are prepared to reset your breakpoints!

You can see a list of all the break points that you have by typing info break. Here is an example of the output when I have one breakpoint at the start of the main function.

(gdb) info break

Num Type Disp Enb Address What

1 breakpoint keep y 0x00000000400dbd in main at bomb.c:37

There are three important fields here:

- NUM: every breakpoint is given a number, which is unique to that session of GDB. This means that each time you set a new breakpoint, it will get a new number. If you delete a breakpoint and put a new one in the same place, it still gets a new number.

- ENB: Whether or not the breakpoint is enabled. This is important becuase if you disabled a breakpoint, it will no longer protect that part of the code from executing.

- ADDR/WHAT: These are more or less one field, and they represent where the breakpoint is. Notice that the what field gives the C code line for main, which is in this case 37. Those line numbers are not useful to us mostly because we don’t have the full code to reference. The important address for us is the hex address, which represents where that function is in memory.

The syntax for adding a breakpoint is very simple: break <expression> or b <expression>

# Example: Adding a breakpoint at <main+40>

(gdb) b *main + 40

Breakpoint 4 at 0x400de5: file bomb.c, line 54.

(gdb)

Ignore the expression used in this example. We will cover expressions later.

The two most important places you can add a breakpoint are:

- At the beginning of a function, which you do by typing

b function_name - At your current location by typing

borbreakwith no argument given.

Once you have placed a breakpoint, you can enable it: enable <num> and disabled it: disable <num>, which essentially turns it on and off. Breakpoints are always enabled when first created.

# Example cont.

(gdb) disable 4 # next time it hits <main+40>, it will not stop

(gdb)

If you want to delete a breakpoint: delete <num>

# Example cont.

(gdb) delete 4

(gdb)

While enable, disable, and delete don’t give any output, you can see the changes you made if you type info break again.

Printing Values

There are two kinds of print in GDB: printing, and examining. In essence, you use print for variables, and examine for pointers. The GDB reference sheet lists them as

-

p- show value of <expr> (or last value $) according to format f -

x- examine memory at address <expr>; optional format spec follows slash

printing values

The structure for print is:

p/f

where f can be any of the following values:

- x - hexadecimal

- d - signed decimal

- u - unsigned decimal

- o - octal

- t - binary

- a - address

- c - character

- f - floating point

examining values

The structure for examine is similar to print, but with two more specifiers:

x/Nuf

N is the number of elements to print.

u is the unit size, which can be any of the following:

- b - single byte (1 byte)

- h - halfword (2 byte)

- w - word (4 byte)

- g - giant word (8 byte)

Note: Remember to keep in mind big-endian vs. little-endian when analyzing larger chunks of memory.

f is the same list as before, with two new additions:

- s - null terminated string

- i - machine instruction

Thought Exercise: Why is it that you can use s and i modifiers for examine and not print?

examples

The expressions used in this section are explained in the following section.

Example 1: Pring out the value stored in %rax as a decimal

(gdb) p/d $rax

# f = d (decimal)

Example 2: Print out the address stored in %rsp

(gdb) p/a $rsp

# f = a (address)

Example 3: Print 4 Units of Hexadecimal memory

(gdb) x/4x $rsp

# N= 4, u = not specified, f = x (hex)

the default u is 4; x/4u = 4x4 = 16 bytes. The memory will print starting from the address specified in %rsp.

Expressions in GDB

Expressions in GDB are similar to expressions in C (in fact, most of the time they are C expressions). I don’t have a comprehensive way to list all the things you can do, because its quite extensive, but I will try to list the some important things for you to know. I will give several examples, all of which will be prefixed by the basic print command, which you can replace with whatever command uses an expression.

basic usage

Let’s start with the types of arguments you can use:

Registers: prefixed with a $ symbol (which differentiates them from program variables that might have the same name).

print $rsp

Function Pointers: must be dereferenced before you use them:

print *main

Constants: can be used without any prefix.

print 0xfffffff6b50

In addition to arguments, GDB supports an almost identical set of operators to C:

- Operators like

*,&,+,-,*, and/work similarly to C but are specifically useful in the context of GDB when working with memory addresses, registers, and pointers. - Bitwise operators (like

&,|,^,<<,>>) are useful for inspecting and manipulating data at the bit level, which is a common need when analyzing assembly and memory in GDB. - Comparison and logical operators follow C syntax but allow GDB to evaluate expressions dynamically as part of the debugging process.

While you can do many crazy expressions, to solve the phases of the bomb lab you will probably only need to know how to reference registers, and maybe do pointer addition with the + operator. Remember, simpler is better.

advanced usage

Please note that this part of the document will likely require some experimentation to print or find what you want. You don’t need to know very advanced expression usage to get through the bomb, so this is mostly just for your learning.

As mentioned before, GDB expressions are essentially C expressions, with the exception that they live outside of the program. What this means is that you can write any expression as long as it follows the following rules:

- It cannot require more than one line to execute

- It must use variables and values that are already in the scope of the running program

- It must return a single value appropriate for the expression at hand.

Here are some examples of some advanced C expressions you could do:

(gdb) print *(int*)($ebx + 4) # Evaluates the memory at ($ebx + 4) as an integer

(gdb) print *(char **)0x7fffffffe560 # Treats 0x...560 as a char double pointer, dereferences it to get the string

(gdb) print *(double*)($esp + 8) # Interprets memory at ($esp + 8) as a double

You can also call some C functions within an expression if you find it helpful:

(gdb) print address(main) # Prints the address of main

(gdb) print strlen($rax) # Assumes $rax is a str pointer and prints the length

(gdb) print offsetof(struct, field) # Allows you to see the offset in memory of a struct

There is also special syntax for expressing an array:

print array[0] # prints the first element, as you would expect

print *array@5 # prints 5 elements from starting point *array

Conclusion

At this point, if you have read everything in this document, you have all the info that you need to stop Dr. Evil’s plan and defuse your bomb. There is also a help video posted here that you can watch that goes over most of these things in a visual way. That video also gives you more insight on how to attack the assembly code. Remember the following tips:

- Start big. Don’t immediately dive into single instructions to determine what they are doing and why they are in that order. Instead, try to create a big picture idea of what’s happening, either in words or pictures. See what the whole function is doing, then “attack” portions of the code to figure out what’s happening to your input.

- None of the names used in this lamb are misnomers - if a function is named

add_two_numbers, then it is guaranteed to add two numbers. Use the names of functions to make assumptions and save yourself time.- Speaking of function names, if a function’s name starts with

iso_c99it is a C library function. You should usually avoid stepping into these; they can be quite complex. You can get away with just knowing what parameters they take and what they return.

- Speaking of function names, if a function’s name starts with

- Try to assess specific portions of that code where your input seems to fail at. By identifying specific failure points like

cmpandtestlines, you can work backwards to identify what the input you gave was, and what it could have been to pass those tests. - Make sure you write everything down! Keep pen and paper on hand. Even if you are making smooth progress, you will want to refer to old structures etc., and unless you finish the bomb in one sitting, you’ll want to make sure you have a good amount of notes on hand when you come back for round 2.

- Remember to go to TA hours, which are usually extended right aroung the time the bomb starts.

Good luck.

Appendices

Appendix A: SSHing into the Digital Lab Machines

both these methods have been re-tested as of 11/9/24. If they don’t work for you, come into TA hours to get help. It’s likely a problem specific to your machine.

Method 1: Double Tunnel

You must first SSH into ssh.et.byu.edu with your CAEDM username and password. From there, you can SSH into a Digital Lab computer, digital-##.ee.byu.edu, where ## can be a number 01 to 60 (you can choose any number, and two people can use the same number). Again, use your CAEDM username and password to log into those machines. For example, run the following commands

ssh username@ssh.et.byu.edu

# Once SSH'd into the CAEDM computer

ssh username@digital-##.ee.byu.edu

Replace username with your CAEDM username and ## with the number of the Digital Lab computer you want to log into.

Method 2: CAEDM VPN

You can use the CAEDM VPN to appear to be on campus and ssh into a machine. Here are the quick facts:

Servername: vpn.et.byu.edu

Protocol: IKEv2

Authentication: EAP-MSCHAPv2

If you don’t already know how to set up a VPN, go to the CAEDM VPN page and scroll to the bottom, where you will find a table of link to setting up the VPN depending on your operating system. After you have gotten the VPN to connect succesfully, your computer will appear to be coming from inside the CAEDM network. This means that you can SSH in directly with ssh username@digital-##.ee.byu.edu, where username is your CAEDM username, and ## is any number between 01 and 60.

If you work in the Engineering Building or Clyde Building in a research position, and already have a VPN set up for that lab, you can try reaching digital-##.ee.byu.edu directly with that VPN enabled instead of creating a new one. The “farther” (virtually) your lab is from the EB’s main subnet, the less likely this is to work.

Appendix B: Additional Resources

-

Compiler Explorer -> Compare C code with its corresponding assembly code.

Looking for a particular tool? How about documentation? Don’t forget, the commands apropos, man, and info are your friends. In particular, man ascii might come in useful. info gas will give you more than you ever wanted to know about the GNU Assembler. Also, the web may also be a treasure trove of information. If you get stumped, reach out to the TAs, and then the instructor.

Appendix C: Using Objdump

There are some cases, mostly in the beginning of the bomb lab, where you may find it helpful to create certain “dumps” of information about your program. When compilers generate output code, many of the variable names, function names, etc. are kept within the code in a symbol table. Below are a few outputs you can use to assist you while defusing the bomb.

Remember: you can save the output of a command to a file by appending the > character and a filename to the end of the command.

Object Dumps

objdump -t

This will print out the bomb’s symbol table. The symbol table includes the names of all functions and global variables in the bomb, the names of all the functions the bomb calls, and their addresses. You may learn something by looking at the function names!

objdump -d

Use this to disassemble all of the assembly code in the bomb. You can also just look at individual functions. Reading the code can tell you how the bomb works.

Although objdump -d gives you a lot of information, it doesn’t tell you the whole story. Calls to system-level functions are displayed in a cryptic form. For example, a call to sscanf might appear as:

8048c36: e8 99 fc ff ff call 80488d4 <_init+0x1a0>

To determine that this specific call was to sscanf, you would need to disassemble the code within GDB.

String Dumps

strings

This utility will display the printable strings in a file.